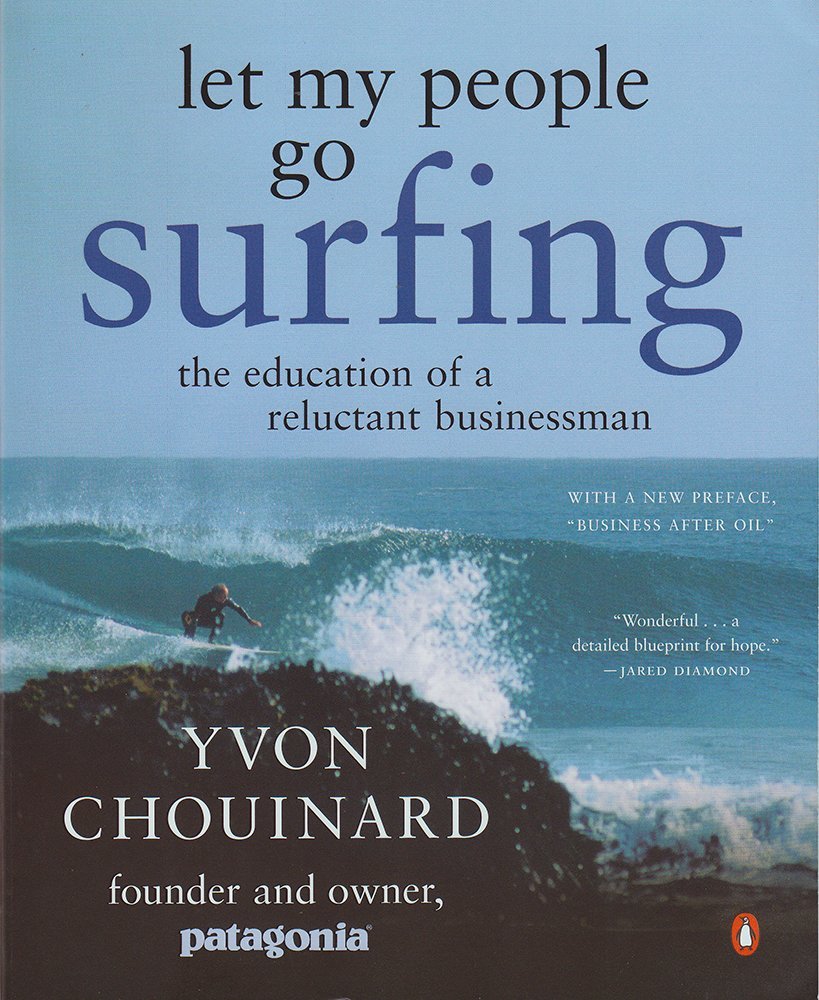

Let My People Go Surfing

I came for the business story, but stayed for the design advice 🤷♂️ Patagonia’s design and production philosophies are very effective and can be easily applied to other fields. I always appreciate all the thinking and attention to details that are present in their clothing.

The way their business being run is really interesting as well. Recently I listened to a podcast with Ricardo Semler, and while reading Yvon’s book I couldn’t stop thinking how much ahead of time their companies were. They built them in the 70s and 80s, but when I read a similarly minded Getting Real by Basecamp (then 37signals) in 2006 it sounded absolutely groundbreaking. Good to know that these ideas predate internet companies and startups.

These interviews with Yvon Chouinard are interesting as well:

History

QA and dogfooding:

Quality control was always foremost in our minds, because if a tool failed, it could kill someone, and since we were our own best customers, there was a good chance it would be us!

On experimentation and perfection:

It is as if there were a natural law which ordained that to achieve this end, to refine the curve of a piece of furniture, or a ship’s keel, or the fuselage of an airplane, until gradually it partakes of the elementary purity of the curve of the human breast or shoulder, there must be experimentation of several generations of craftsmen. In anything at all, perfection is finally attained not when there is no longer anything to add, but when there is no longer anything to take away, when a body has been stripped down to its nakedness.

That reminded me of Walt Disney's famous quote “We don’t make movies to make money, we make money to make more movies”:

None of us saw the business as an end in itself. It was just a way to pay the bills so we could go off on climbing trips.

On creating a fashion for outdoorsy look:

The rugby shirt’s sales had become a burgeoning underground fashion in the mountain shops. These stores shared our heritage; they had been started by climbers and backpackers who knew little about business but needed a way to support themselves. Originally they had found unexpected growth from the college fad of wearing Vibram-soled mountain boots to class and down jackets around the city.

On Patagonia’s guiding principle:

Since I had never wanted to be a businessman, I needed a few good reasons to be one. One thing I did not want to change, even if we got serious: Work had to be enjoyable on a daily basis. We all had to come to work on the balls of our feet and go up the stairs two steps at a time. We needed to be surrounded by friends who could dress whatever way they wanted, even be barefoot. We all needed to have flextime to surf the waves when they were good, or ski the powder after a big snowstorm, or stay home and take care of a sick child. We needed to blur that distinction between work and play and family.

On Esprit and The North Face:

I didn’t find any American company we could use as a role model. Either it was too large and conservative for us to relate to, or it didn’t have the same values. However, there was one company, Esprit, owned by my friends Doug and Susie Tompkins, that was contrary and that shared our values. Doug was a climbing and surfing friend who in the early sixties started The North Face store in San Francisco.

It’s pretty amazing that multiple successful companies were founded by the people from the same small circle. Even more amazing considering how focused they were on things unrelated to building a business.

On being an 80 percenter:

I’ve always thought of myself as an 80 percenter. I like to throw myself passionately into a sport or activity until I reach about an 80 percent proficiency level. To go beyond that requires an obsession and degree of specialization that doesn’t appeal to me. Once I reach that 80 percent level I like to go off and do something totally different; that probably explains the diversity of the Patagonia product line—and why our versatile, multifaceted clothes are the most successful.

That resonated a lot with me. I love trying new stuff, but usually switch to something else as soon as I get reasonably proficient. There are only a few things that I’ve been deeply interested in for years.

On rough prototyping:

Our first pile garments, stiff with their sizing treatment, were made from fabric intended for toilet seat covers.

On not waiting till you get all the answers:

Yet you can’t wait until you have all the answers before you act. It’s often a greater risk to phase in products because you lose the advantage of being first with a new idea.

On Patagonia’s HQ:

That year we built a new Lost Arrow administration building that had no private offices, even for the executives. This architectural arrangement sometimes created distractions but helped keep communication open. Management worked together in a large open area that employees quickly dubbed the corral. We provided a cafeteria that served healthy, mostly vegetarian food where employees could gather throughout the day. And we opened, at Malinda’s insistence, an on-site child care center, Great Pacific Child Development Center, Inc.

On growing a company:

Can a company that wants to make the best-quality outdoor clothing in the world be the size of Nike? Can a ten-table, three-star French restaurant retain its third star when it adds fifty tables? Can you have it all? The question haunted me throughout the 1980s as Patagonia evolved.

On Russia:

On a kayaking trip to the Russian Far East, before the collapse of the Soviet Union, I found that the Russians had destroyed much of their country trying to keep up with the United States in their arms race. Their oil, mineral, and timber extraction had devastated the land, and failed industrial efforts had contaminated cities and farmlands. They were eating their seed corn.

On Black Diamond Ltd. (another successful company!):

Our insurance premiums went up 2,000 percent in one year. Eventually Chouinard Equipment Ltd. filed for Chapter 11, a move that gave the employees time to gather capital for a buyout. They successfully purchased the assets, moved the company to Salt Lake City, and built their own company, Black Diamond Ltd., that to this day continues to make the world’s best climbing and backcountry ski gear.

On their approach to product management:

To re-create the entrepreneurial atmosphere of the sort we’d had at Chouinard Equipment, we broke the line into eight categories and hired eight product czars to manage them. Each was responsible for his or her own product development, marketing, inventory, quality control, and coordination with the three sales channels—wholesale, mail order, and retail.

…and why it didn’t work:

Looking back now, I see that we made all the classic mistakes of a growing company. We failed to provide the proper training for the new company leaders, and the strain of managing a company with eight autonomous product divisions and three channels of distribution exceeded management’s skills. We never developed the mechanisms to encourage them to work together in ways that kept the overall business objectives in sight.

On company culture:

While my managers debated what steps to take to address the sales and cash-flow crisis, I began to lead weeklong employee seminars in these newly written philosophies. We’d take a busload at a time to places like Yosemite or the Marin Headlands above San Francisco, camp out, and gather under the trees to talk. The goal was to teach every employee in the company our business and environmental ethics and values. When money finally got so tight we couldn’t afford even to hire buses, we camped in the local Los Padres National Forest, but we kept training.

On exceeding your limits:

I had always tried to live my own life fairly simply, and by 1991, knowing what I knew about the state of the environment, I had begun to eat lower on the food chain and reduce my consumption of material goods. Doing risk sports had taught me another important lesson: Never exceed your limits. You push the envelope, and you live for those moments when you’re right on the edge, but you don’t go over. You have to be true to yourself; you have to know your strengths and limitations and live within your means. The same is true for a business. The sooner a company tries to be what it is not, the sooner it tries to “have it all,” the sooner it will die.

Philosophies

On empowering by sharing a philosophy:

At Patagonia, these philosophies must be communicated to everyone working in every part of the company, so that each of us becomes empowered with the knowledge of the right course to take, without having to follow a rigid plan or wait for orders from a “boss.”

Product Design Philosophy

Here are the main questions a Patagonia designer must ask about each product to see if it fits their standards.

Is It Functional?

Designing from the foundation of filling a functional need focuses the design process and ultimately makes for a superior finished product. Without a serious functional demand we can end up with a product that, although it may look great, is difficult to rationalize as being in our line—i.e., “Who needs it?”

Is It Multifunctional?

The best products are multifunctional, however you market them. If the climbing jacket you bought to ski in can also be worn over your suit during a snowstorm in Paris or New York, we’ve saved you from having to buy two jackets, one of which would stay in the closet nine months of the year. Buy less; buy better. Make fewer styles; design better.

Is It Durable?

Someone once said that the poor can’t afford to buy cheap goods. You can buy a cheap blender that will burn out the first time you try to grind some ice cubes, or you can wait until you can afford a quality one that will last. Ironically, the longer you wait, the less you may have to spend; at my age, it’s becoming easier to buy only products that will “last a lifetime.”

Does It Fit Our Customer?

Is It as Simple as Possible?

Is the Product Line Simple?

Is It an Innovation or an Invention?

Is It a Global Design?

Is It Easy to Care For and Clean?

But environmental concerns trump all others. Ironing is an inefficient use of electricity, washing in hot water wastes energy, and dry cleaning uses toxic chemicals. Machine drying, far more than actual wear, shortens the life of a garment—just check the lint filter!

The most responsible way for a consumer and a good citizen to buy clothes is to buy used clothing. Beyond that, avoid buying clothes you have to dry-clean or iron. Wash in cold water. Line dry when possible. Wear your shirt more than one day before you wash it. Consider faster-drying alternatives to 100 percent cotton for your travel clothes.

Does It Have Any Added Value?

Is It Authentic?

Is It Art?

Are We Just Chasing Fashion?

Are We Designing for Our Core Customer?

To understand this more clearly, we can look at our customers as if they existed in a series of concentric circles. In the center, or core circle, are our intended customers. These people are the dirt-baggers who, in most cases, have trouble even affording our clothes.

Have We Done Our Homework?

Some people think we’re a successful company because we’re willing to take risks, but I’d say that’s only partly true. What they don’t realize is that we do our homework.

Is It Timely?

To stay ahead of the competition, our ideas have to come from as close to the source as possible. With technical products, our “source” is the dirtbag core customer. He’s the one using the products and finding out what works, what doesn’t, and what is needed. On the contrary, sales representatives, shop owners, salesclerks, and people in focus groups are usually not visionaries. They can tell you only what is happening now: what is in fashion, what the competition is doing, and what is selling. They are a good source of information if you want to be a player in the “cola wars,” but the information is too old if you want to have leading-edge products.

Does It Cause Any Unnecessary Harm?

Production Philosophy

Six production principles that are crucial to the faithful execution of designs.

- Involve the Designer with the Producer

- Develop Long-term Relationships with Suppliers and Contractors

- Weigh Quality First, Against On-Time Delivery and Low Cost

- Go for It, but Do Your Homework

- Measure Twice, Cut Once

- Borrow Ideas from Other Disciplines

Distribution Philosophy

On building a redundant distribution system:

Yet very few companies other than Patagonia sell their products at a wholesale level to dealers, sell through their own retail stores, through mail order, and through the Internet, and do it all worldwide. This diversity of distribution has been a tremendous advantage for us. In a recession, when our wholesale sales are down, our direct sales channels do well because there is no lessened demand for our goods from our loyal customers.

Image Philosophy

On word of mouth:

Talking about ourselves to our parents on the phone is fine, but in every other situation the word from outside carries more weight.

Financial Philosophy

It’s okay to be eccentric, as long as you are rich; otherwise you’re just crazy.

On quality and business success:

That report has begun to show quite clearly that quality, not price, has the highest correlation with business success. In fact the institute has found that overall, companies with high product and service quality reputations have on average return-on-investment rates twelve times higher than their lower-quality and lower-priced competitors.

On staying private:

We are a privately owned company, and we have no desire to sell the company or to sell stock to outside investors, and we don’t want to be financially leveraged. In addition, we have no desires to expand Patagonia beyond the specialty outdoor market.

On staying small:

We don’t want to be a big company. We want to be the best company, and it’s easier to try to be the best small company than the best big company.

On staying debt-free:

Because of our pessimism about the future of a world economy based on limited resources and on endlessly consuming and discarding goods we often don’t need, not only don’t we want to be financially leveraged, but our goal is to have no debt.

Human Resource Philosophy

On passion of their employees:

We have employees who never sleep outside or who have never peed in the woods. What they all do share, as our organizational development consultant noted, is a passion for something outside themselves, whether for surfing or opera, climbing or gardening, skiing or community activism.

Management Philosophy

On personal responsibilities and small cities:

This is an extension of the fact that democracy seems to work best in small societies, where people have a sense of personal responsibility. In a small Sherpa or Inuit village there’s no need to hire trash collectors or firemen; everyone takes care of community problems. And there’s no need for police; evil has a hard time hiding from peer pressure. The most efficient size for a city is supposed to be about 250,000 to 350,000 people, large enough to have all the culture and amenities of a city and still be governable—like Santa Barbara, Auckland, and Florence.

Environmental Philosophy

On nutrition:

A study by the UK’s Medical Research Council in 1991 showed that vegetables had lost up to 75 percent of their nutrients since 1940, meats had lost half their minerals, and fruits had lost about two-thirds.

On wilderness:

The place in the lower forty-eight states that is farthest away from a road or habitation is at the headwaters of the Snake River in Wyoming, and it’s still only twenty-five miles. So if you define wilderness as a place that is more than a day’s walk from civilization, there is no true wilderness left in North America, except in parts of Alaska and Canada.

Wilderness says: Human beings are not paramount, Earth is not for Homo sapiens alone, human life is but one life form on the planet and has no right to take exclusive possession.

On curiosity and examined lives:

Uncurious people do not lead examined lives; they cannot see causes that lie deeper than the surface. They believe in blind faith, and the most frightening thing about blind faith is that it in turn leads to an inability, even an unwillingness, to accept facts.

On wool:

Let’s take wool, for example. Wool can be very damaging or benign, depending on whether the sheep are grazing in fragile desert environments and alpine meadows or in areas with frequent rain, plenty of natural grass, and no predators. Wool also often relies on chemicals at every stage. The sheep are dipped in pesticides to kill parasites; the fleece is scoured with petroleum-based detergents; the yarn is bleached with chlorine and then dyed with heavy metal–based dyes. The workers exposed to the chemical sheep dips may suffer neurological damage. Orlon, a synthetic substitute for wool, is made from oil and is therefore not sustainable, so it seems that using any kind of wool would be a more natural and sustainable option than a synthetic substitute. But if you wanted to replace the output of one Orlon mill with wool, you would have to devote every acre from Maine to the Mississippi exclusively to the raising of sheep. In fact at our present rate of consumption, we can no longer clothe the world with natural fibers.

On why cotton is bad:

Even when cotton is grown without toxic chemicals, it still uses an inordinate amount of water and cannot be grown year after year without permanently depleting the soil.

Read from December 21, 2017 to December 30, 2017 .